OK … yeah … let’s have the oil discussion. I know we’re not supposed to because internet and reasons, but it’s got to happen sooner or later. Your Airhead needs two, maybe three different kinds of oil throughout an entire year of riding and there’s no sense in putting off the discussion any more. You’re becoming more mature as a rider and I’m sure you can handle this knowledge.

For the purposes of this discussion, let’s define “Airheads” as specifically the Slash 5, 6 and 7 generations; that is, BMW motorcycles produced for the 1970 to 1978 model years. These models have a lot of similarities, though later models are also called Airheads as well. Their names are followed by a /5, /6 or /7, but may instead be followed by an S or other letters from 1974 on. After the 1978 model year, BMW dropped the “slash” notation. “Pre-Airheads” are BMW motorcycles produced for the 1955-69 model years and consists of just a few variations: R 50, R 60 and R 69. These model names may be followed by nothing, a /2 or US. The vast majority of motorcycles produced by BMW during this period range from about 500 to 1,000 cubic centimeters of displacement, or about 30 to 61 cubic inches. Some of the information in this article will also apply to later Airheads, from 1980 through 1994, though there are subtle variations that may apply to your particular motorcycle. Refer to your owner’s manual or email me if you have questions.

There are four systems which require oil in them for proper operation: the engine (of course), transmission, swingarm and final drive. The engine requires engine oil, while the other systems require gear oil. The swingarm doesn’t need the oil, it’s the lower end of the drive shaft that needs it, but you provide that oil by pouring it into the swingarm.

Before I dive into this, a note: We live in a world in which excessive reliance on the opinions of random people on the internet both carries disproportional weight and runs a high risk of explosive disagreement. Rest assured I will be giving you conservative, middle-of-the-road advice here, because that’s my style. Better safe than sorry, in other words, and this is what I do with my two vintage Beemers, a 1966 R 60/2 and a 1976 R 90/6, and my 2015 R 1200 GS.

When people tell you not to start a discussion about oil in polite company, this is typically the kind of oil to which they refer. It’s easy to get confused or make assumptions these days, especially when we’re managing the modern technology of our newer bikes and other vehicles like cars, light trucks and SUVs while trying to hold onto the knowledge we need for our older bikes. It’s a little sad that my 2015 motorcycle is in some circles considered an older bike, but this is the world in which we live now.

First, I’ll get into some definitions for terms you’re going to see in this article and online discussions about the topic.

- Dinosaur oil: Refers to any oil of a purely organic and/or mineral nature. The term comes from our usage of “fossil fuels,” give that those oil deposits various companies pull from under the earth’s surface were created over millions of years by decaying organic matter. Finding a true, 100% pure organic/mineral oil in the 21st century is not always easy, nor is it particularly inexpensive. These have become the boutique products as man-made production has taken over the industry.

- Semi-synthetic oil: Refers to any oil that is a mixture of organic and man-made materials. Manufacturers typically do not disclose what the percentages are. These consist of an organic base oil supplemented with man-made materials or vice-versa. Unless the label says “fully synthetic” or “100% synthetic,” you’re using a semi-synthetic oil.

- Synthetic oil: Refers to any oil with man-made base stocks rather than dinosaur bases.

- SAE: The Society of Automotive Engineers is the group setting the temperature ratings and performance requirements of the oils we use in our vehicles. All oil ratings mentioned in this article should be assumed to have “SAE” in front of them.

- W: Often mistakenly thought to refer to “weight,” the W in your oil refers to its “winter” rating, meaning how it operates at low temperatures. If your oil weight (viscosity rating) has two numbers separated by a W, the first number refers to its winter rating, the second to its standard rating. All oils of this type use viscosity index improvers whether the base oils are dinosaur or synthetic. Common designations are 10W40, 15W50, 20W50, 75W90, 80W90, etc.

- Weight: Refers to the viscosity of a given oil used in its normal temperature range. Thinking of it as “thickness” or “flowability” rather than “weight” might help you form a more appropriate mental picture of the oil’s performance. ALL oil becomes more viscous as temperature falls; hot oil flows more easily, which is less viscous. Water has low viscosity; honey has high viscosity.

Semi-synthetic oils for automotive use go back further than you probably imagine, with the first multigrade oil appearing in Europe in the early 1950s, followed by the first true semi-synthetic oil coming in 1966. The first fully synthetic oil was produced in 1971. Mobil 1, possibly the most well-known synthetic oil, found wide distribution in 1976; its development was spurred by the oil crisis of the 1970s. While some manufacturers specified their use early on, most waited until these oils were more reasonably priced for consumers—i.e. their factories, not necessarily the end users.

Engine Oil

Before the widespread use of multigrade oils, most motor vehicles used “straight weight” oils rated 20, 30, 40 or 50—referred to as “30 weight” and so on. The first multigrade oils used in passenger cars in the 1960s were 10W40 and 15W40. Various iterations from there developed over time, and by the late 1980s and early ‘90s, when I was getting into motorcycling, I used both of those oils in addition to 20W50, which was the spec in my first BMW, a 1996 R 1100 GS. The owner’s manual recommended 10W40 in extremely cold temperatures, but suggested 20W50 was a better all-around choice.

There is a common misperception that, in an oil rating, the numbers refer to temperatures—that is, that “20W50” means “20 degrees.” That’s not correct. What it really means is that the oil meets the viscosity requirements of 20-weight oil at 14° F (-10° C) and 50 weight at 212° F (100° C). (NOTE: Some multigrade oils are tested at -30° F/-35° C to determine their lower designation. Refer to the manufacturer’s fact sheets.) Most oil bottles don’t tell you what those temperatures are, though! Here’s a handy reference chart for the various weights and ambient—that is outdoors wherever you are—temperatures. Naturally, the temperatures inside your engine will be higher once it gets going, sometimes reaching 200° F (94° C) or even a bit more.

| Viscosity Rating | Minimum Temp (°F) | Maximum Temp (°F) |

| 30 | 15° | 95° |

| 40 | 25° | 115° |

| 0W30 | -30° | 95° |

| 5W40 | -20° | 105° |

| 10W40 | -15° | 105° |

| 15W40 | -5° | 105° |

| 20W50 | 5° | 115° |

Between 68-140° F (20-60° C), straight 40 weight oil behaves quite similarly to 20W50. Below that (32-86° F or 0-30° C), it is more viscous and as expected, above that range, it is less viscous. As the temperature rises, the viscosity of 40 weight oil lessens more quickly than that of 20W50. You can make similar comparisons between 30 weight oil and 10W40. When you look at the original specs for BMWs from the 1950s and ‘60s, it should be no surprise to see 30 noted for winter use and 40 for the rest of the year.

BMW Motorrad specifies 5W40 oil for my 2015 R 1200 GS, with additional requirements that it be rated API SL and JASO MA2. (More on those designations later.) This type of oil is suitable for standard operation in ambient temperatures from -22° to 104° F (-30° to 40° C) However, the spec for my 1976 R 90/6 is 20W50 for most of the year and 10W40 in the winter during sustained low temperatures. I have never put 10W40 in it because I simply don’t ride under the minimum rating for 40-weight oil (25° F/4° C) on a regular basis.

Because straight-weight oils do not enjoy the enhanced chemistry and extended operating ranges of blended oils, they will deteriorate more quickly and lose their ability to lubricate all the internal moving parts and suspend the byproducts of combustion in solution. This is one of the reasons the older BMW motorcycles tending to use these oils have “slingers” in them. Slingers are discs with U-shaped lips on either end of the crankshaft that use centrifugal force to trap solids in the oil supply. The lips of the slingers eventually become packed full of these solids and must be cleaned or replaced; doing so requires removing the crankshaft from the engine case, no simple task. Every time you change the oil filter in your BMW from 1970 or later, thank all your icons and totems you don’t have slingers in your engine.

Motor oils are subjected to two types of “shear”—temporary shear, when the molecules are squashed but spring back into shape, and permanent shear, when the molecules are compromised to the point they break apart into their smaller component parts. Oil is sheared when it’s forced through a small opening; if the opening is too small, the oil molecules rupture. What determines whether an opening is too small or not is the viscosity rating of the oil and, of course, the operating temperature at which the squash occurs.

Resisting shear is exactly why multigrade oils exist. When your engine is cold, all the metal inside exists at a certain size. The metals heat up while you ride, so all those parts expand at some predictable rate, reducing the clearance between parts. A straight weight oil might be too thick to flow properly at low temperatures, but be perfect for higher temps. With multigrade oils, your engine gets the benefits of lower viscosity at low temps and higher viscosity at high temps, coming as close to the best of both worlds as manufacturing technology can get.

API and JASO

Let’s take a look at the other designations attached to the oil we use: API and JASO. The American Petroleum Institute rates the anti-wear additive packages and performance levels of oils at any operating temperature; these ratings will correlate more closely to the anti-shear characteristics than the viscosity ratings established by the SAE. They periodically update their ratings, which for engines burning standard gasoline have so far been two-letter marks starting with SA and ending with SP. One assumes they’ll have to dip into another starting letter or start adding letters or numbers after they get to SZ. All API ratings from SA to SH are considered obsolete in 2026; current ratings are SN (for 2020 and older vehicles) and SP (for vehicles built since May 2020, including those able to burn E85 fuels, but with some backwards compatibility with SN). Based on the API charts, my 2015 R 1200 GS should require SN-rated oil, but the owner’s manual specifies SL, which means BMW’s 2015 liquid cooled boxer engines are, in some ways, not made with tolerances and requirements too different from the first (air/oil cooled) 1200cc boxers.

In their days, my 1966 and 1976 Beemers required API SC and SE oils, respectively. Even if these oils were available in modern times, using them in modern vehicles wouldn’t be ideal. These older oils simply don’t have the additives needed to prevent the buildup of sludge in the oil, oxidation on internal surfaces or excessive wear in metal-on-metal situations. However, modern SL, SM, SN or SP oils may not have the levels of additives those 1960s and ‘70s German engineers were expecting, and in the case of the R 60/2, better-performing additive packages might actually be detrimental to the engine over the long term. This is one of the reasons I change the oil in the Slash 2 every 1,000 miles—but that’s a topic for a future article.

While API designations are for any oil, the Japanese Automotive Standards Organization has designations specifically for motorcycles, largely because many (most?) motorcycles in the world use a wet clutch. Unlike BMW boxers before 2014—which certainly includes my vintage Beemers—Moto Guzzis and some Ducatis, which all have dry, automotive-style clutches, BMWs with wet clutches have to use oil that will both lubricate the internal engine parts and cool the clutch plates without causing them to slip. It’s a lot to ask, frankly, and it’s the main reason it’s critical that you know what kind of clutch your bike has before you change the oil in its engine. Bikes with dry clutches can use “regular” engine oil; those with wet clutches must must must! Use oils specifically engineered for that use case.

My R 1200 GS requires oil rated JASO MA2, which means the oil is engineered to function properly with a four-stroke engine and a wet clutch, and has acceptable levels of certain friction modifiers. MA and MA1-rated oils do not contain these friction modifiers. Oils rated MB are intended for use in dry clutch motorcycles. Additionally, to attain a JASO rating, the oil must also be API certified (SG to SM), or have a specific certification from ILSAC (a joint U.S.-Japan organization) or ACEA (Europe), further cementing the idea that JASO is really looking out for us motorcycle riders. The requirements underlying all of these ratings is JASO T 903:2006, which is so technical that I started to lose my mind within three minutes of trying to read it.

My Engine Oil Choices

I told you all of that so I could tell you this: As long as the oil you buy for your motorcycle meets the minimum standards of the above engineering institutions, it’s probably going to be OK to use with your motorcycle. Beyond that, you simply need to select the proper weight BMW specifies from your favorite brand name. I say brand name on purpose; don’t insult yourself and your motorcycle by buying off-brand oil if you don’t have to. Buying generic groceries is one thing, but when it comes to generic oil, unless you have 100% positive proof it’s made by a reputable manufacturer, spend the extra few dollars and get the name-brand stuff. Your motorcycle will thank you in the long run. This applies to gasoline as well, but that’s a subject for another time.

For my 2015 R 1200 GS, I use Castrol Power1 5W40 Full Synthetic motorcycle oil. It’s rated API SN and JASO MA2. I typically buy it in a six-quart “half case” for anywhere from $50-60, which gives me the four quarts I need for an oil change and two extra for topping up over the course of the next 5,000 miles. Fortunately, my bike doesn’t burn or otherwise use very much oil, so I generally get three oil changes out of two of these half-cases.

For the 1976 R 90/6, I use Valvoline VR1 20W50 Racing Oil. Valvoline has a full synthetic version of this oil, so I believe the oil I buy is semi-synthetic. There is no API or JASO certification listed, either. The primary reason I use this oil is because it has higher proportions of zinc and phosphorus, two additives critically important for these older engines. Both of them help prevent excessive wear. Valvoline claims this oil is great for engines using pushrods and flat tappets like those in our Airheads. I change the oil on this bike every 2,500 miles, and it takes about two and a half quarts. I burn about another full quart between oil changes, so a six-quart half case, which costs me about $50, lasts for two maintenance cycles. If I ever fully rebuild the engine on this bike, I’ll switch to the full synthetic 20W50 VR1.

For the 1966 R 60/2, I stick with Valvoline VR1, but I use the straight 40-weight oil, which is about $50 for a six-quart half-case. Like the 20W50, it’s semi-synthetic, lacks both API and JASO certifications, has elevated levels of zinc and phosphorus and is engineered for engines with pushrods and flat tappets. The Slash 2 takes two quarts for an oil change and I rarely need to top it up, so the half-case gives me three maintenance cycles. In a pinch, I wouldn’t hesitate to put 20W50 in this engine, or even 10W40, but because that’s not what BMW specified, I wouldn’t want to do that regularly or leave it in there for a long time.

Part of the near-religious fervor with which people discuss oil when it relates to the Pre-Airhead (Slash 2) generation of motorcycles is whether or not the oil should have detergents in it. It’s a good thing to think about, but like many other aspects of motorcycle maintenance, those who scream the loudest often are the ones who people listen to, thus perpetuating myths that probably should have died decades ago. The reality is pretty simple, though. If your engine has been recently rebuilt, and the job was done properly, there is no reason to resort to the expense and hassle of tracking down non-detergent oil of the proper weight. If you’re sure the slingers are clean and you change the oil regularly, non-detergent oil is simply not needed. Having said that, if your bike’s odometer is over some multiple of 30,000 miles or was broken for some time before you bought the bike, you can’t know the condition of the slingers without cracking the engine open.

If you have no idea when the last time your slingers were cleaned or replaced, you should consider using non-detergent oil to avoid dislodging the crap built up in the slingers. While evidence is largely anecdotal, there is a chance that as sludge in the slingers is dissolved by the detergents in the oil, it could clog the tiny oil passages in the engine, starving the engine of oil and cause a catastrophic failure. Once you rebuild the engine and clean or replace the slingers, you can safely use detergent oil again, provided you commit to a short maintenance cycle like mine of about 1,000 miles between oil changes. In all honesty, it’s not the presence of the detergents that is the real problem; it’s the possibility of kicking up debris in the oil faster than the slingers can trap it that’s the actual problem.

I should note that many racing oils have minimal detergents or even none at all because the manufacturers likely expect people using them to be changing the oil often and perhaps rebuilding the engines more frequently than a regular motorcycle rider might be doing. Because of those factors, the oil needs fewer detergents because the engine is undergoing regular and sometimes invasive maintenance.

While I’m not committed to any one brand with my R 1200 GS, I still stick to the majors: Amsoil, BMW Motorrad, Castrol, Liqui Moly, Motorex, Motul and Valvoline. The brands that cater to motorcycles tend to cost more—usually about $23 per liter—compared to the bigger brands that make oil for a wider variety of vehicles. Those tend to come in between $10-16 per quart. I trust Castrol partly because they used to manufacture the BMW Motorrad-branded Advantec oil; I don’t know if that relationship is still in place, but the fact that BMW at least used to trust Castrol says a lot to me.

When it comes to the two vintage bikes, I’ll continue using Valvoline VR1. It seems to be the best combination of features and cost, and is easily available via Amazon. My local auto parts stores usually have the 20W50 VR1 in stock, but nobody ever has the 40-weight on the shelf. Another brand I’ve seen some Airhead riders use is Driven GP-1 20W50 Synthetic Blend Racing Oil. It costs about $80 for a six-quart half case, almost 50% more than the Valvoline without appearing to provide better overall performance. Other brands producing oil of this type and weight include Castrol, Penn Grade, Lucas Oil, Schaeffer and VP Racing. Prices vary, as do additive packages, but I’m happy with the Valvoline and disinterested in doing more research to find an alternative.

Gear Oil

Engine oil certainly creates spirited discussions, but they often pale in comparisons to online discourse about gear oil. You’re likely to find just as many opinions about what gear oil to use, but many of them lack the basic research and reasoning most folks put into their engine oil choices. Many times, a rider’s gear oil choice boils down to “this is what I was told to use” and never progresses beyond that.

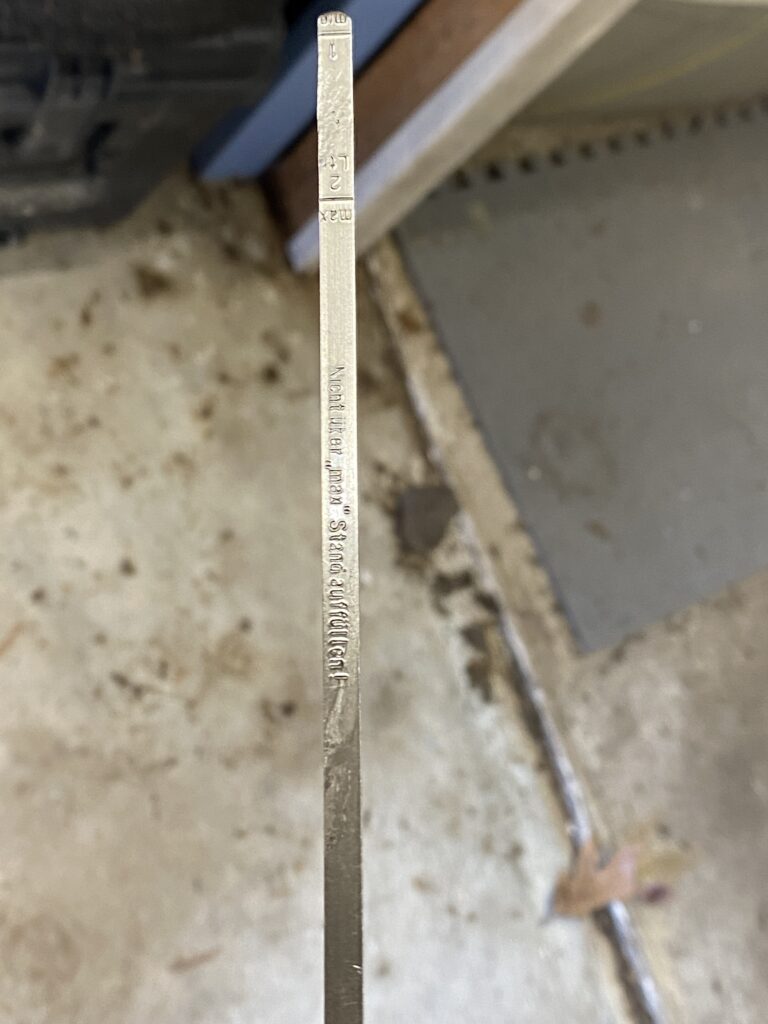

You’d think the owner’s manual would be helpful, but in the case of my 2015 R 1200 GS, what I get in the OM is the gear ratio (2.91, or 32/11 if you were curious). It’s only in digging through BMW Motorrad’s technical documentation—which not every rider has access to—that it’s possible to find the spec for this bike: 75W90 C-SAF-XO. Fortunately, this oil isn’t terribly expensive, but it comes in 200 cc bottles, which leaves little left after I put in the requisite 180 ccs. It’s more cost effective to buy a whole quart of something else and have extra for multiple maintenance cycles. Since most of the arguments on the internet revolve around whether you should use GL-4 or GL-5 oil and C-SAF-XO doesn’t tell you which of those it is, you have to dig if you want any info. (Spoiler: it’s GL-5 oil.)

One of the differences between GL-4 and GL-5 is the additive packages, which helps determine how suitable a given multigrade oil is at handling extreme applications. The GL rating comes from our old friends at the API. They set the most recent standards in 2013, and not much has changed since then. It’s really technical and I’m not sure I understand it all, but I’ll break down the basics for you.

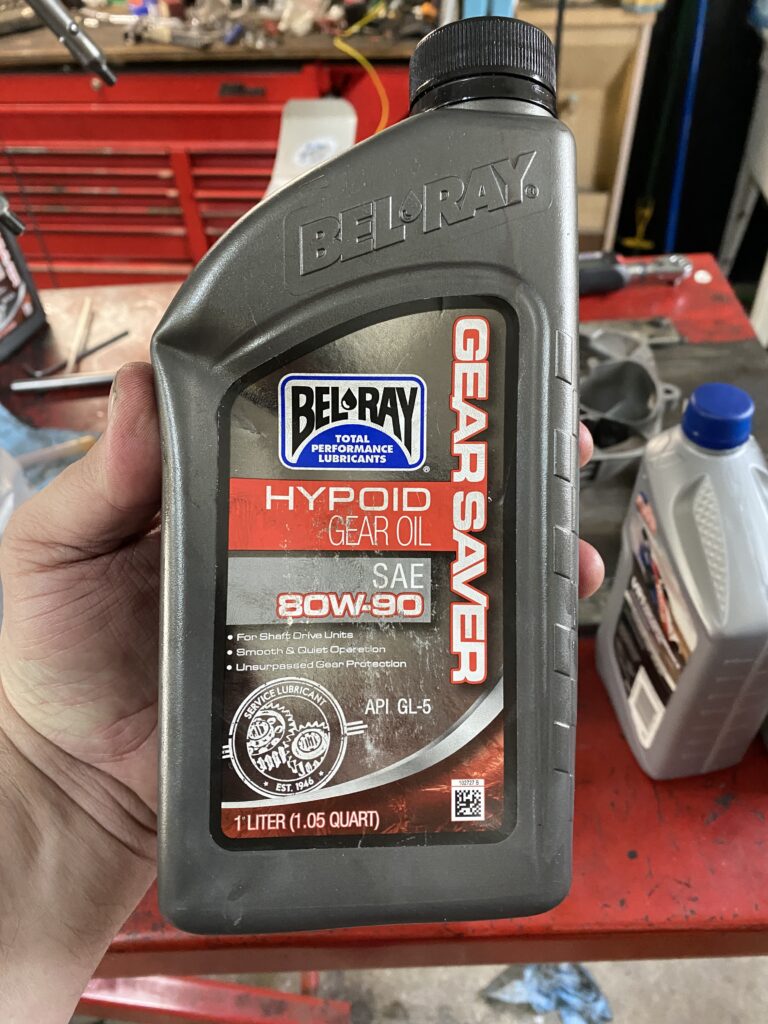

GL-4 gear oil is designed for use with spiral bevel gears being subjected to “moderate to severe conditions of speed and load,” or hypoid gears subjected to moderate conditions. GL-5 gear oil is designed for use with hypoid gears subjected to “high-speed/shock load and low-speed/high-torque conditions.” Gear oil certified as SAE J2360 is an acceptable substitute, as the SAE spec exceeds the API spec. Basically what it comes down to is how the gears are constructed.

Spiral bevel gears are found in the vast majority of BMW motorcycle final drives. Hypoid gears are a variation of spiral bevel gears in which the pinion’s axis is offset from the gear to which it connects, thus creating a higher level of shear than in a standard spiral bevel gear. Hypoid gears can safely operate at higher torque than spiral bevel gears, which explains why BMW started using hypoid gearboxes on its later, more powerful models featuring drive shafts.

Because of the tighter tolerances required to effectively translate the spinning of the drive shaft into the spinning of the drive wheel—or in the case of a bike older than my 2015, the crank shaft—it’s important to use GL-5 gear oil for the most recently manufactured final drives. The good news is that GL-5 oils exceed the mechanical specs of GL-4 oils, which means you can use GL-5 in a slightly older system which requires GL-4, provided, of course that the additive package in the GL-5 oil is chemically compatible. The opposite is not true, however; if your system specifies GL-5, you must not use GL-4 oil. If you do, you risk damaging the system, and damaging your final drive on a motorcycle could mean serious injury or even death.

When it comes to the systems on my vintage bikes that require gear oils, they will do just fine with GL-4 oils, as they are equipped with a variety of straight and bevel gears. That gives me plenty of choices, except for one thing: brass. The transmission and final drive in the R 60/2 both have a few parts made from brass in them, and in case you don’t remember your high school science, brass is softer than steel by a wide margin. It also deteriorates at a different rate based on what chemicals come into contact with it.

Many GL-5 gear oils contain active sulfur, which accelerates the deterioration of brass and bronze parts in older machines like my R 60/2, so I definitely have to be careful not to use that oil. GL-4 gear oils typically contain about half the active sulfur of GL-5 oils, which apparently isn’t a high enough concentration to damage the soft metals—but it’s still not ideal. It’s better to use a GL-4 gear oil fortified with deactivated or buffered sulfur, which will not damage brass or bronze.

When it comes down to the weight of gear oil, you’re going to find 75W80, 75W90, 80W90 and possibly 75W140 and 80W140. The 75/80 W 80/90 oils are going to pretty much perform the same; their temperature ranges are similar and their viscosity curves under temperature and pressure are quite close to each other. In that regard, it’s safe to choose whichever weight is made by a brand you trust. Use GL-5 for modern motorcycles and GL-4 for bikes older than 2000 unless you know for a fact your bike makes use of hypoid gears—or if the manufacturer specifies one oil or the other.

For my R 1200 GS and the R 90/6, I use GL-5 75W90 or 80W90 gear oil. I’m not picky about the brand as long as I’m familiar with it, and have used Liqui Moly ($17/ltr), Lucasoil ($12/qt), Mobil1 ($14/qt), Red Line Heavy Shockproof ($18/qt), Royal Purple ($20/qt) and Valvoline ($13-16/qt) over the years. While I only need about 180 ccs for the final drive on my GS, doing a full service on the Slash 6 requires more than a full quart; the transmission takes 800 ccs, the swingarm 150 and the final drive 250. I avoid mixing weights and brands in a single system, but it doesn’t bother me to use one brand in the transmission and another in the swingarm, for example, if I have a little left over from a previous maintenance cycle. For what it’s worth, the manufacturers recommend against mixing brands as well.

I know my R 60/2 systems have brass parts in them, so that rules out GL-5 oils completely. For that bike, I use VP Classic Hi Performance GL-4 80W90, which costs about $12 a quart. Take my advice and buy it direct from VP Racing to get the lowest prices. Retailers and e-tailers like Amazon all charge a hefty markup. Liqui Moly and Red Line both make GL-4 gear oils, but be careful to avoid anything marked “GL-4+” when it comes to your Slash 2 unless they are specifically stated to be safe for use with soft metals. Those formulations are usually cross-compatible with GL-5 systems, which means you have to pay really close attention to their formulations in order to avoid damage to any brass parts in your systems.

There you have it! All the oils I use for my various BMW motorcycles—plus why I use them—and what all the little letters and numbers on your oil labels represent. Hopefully you’ve got a deeper understanding of the whys and wherefores of motor and gear oil now and will be well equipped to hold your own the next time somebody asks, “So what kind of oil do you think I should use?” Naturally, you don’t have to take that bait, but I’m certainly not going to tell you not to do it!

Service Intervals and Cost

1966 R 60/2: Pre-Airhead engine oil change intervals are specified every 2,000 miles once the bike is broken in; I do mine every 1,000 miles, partly because the bike doesn’t get ridden as often as my other bikes, which means dirty oil tends to sit in the engine for longer periods. BMW also wants you to check the transmission, final drive and swing arm oils at 4,000 miles, but not to change them until 8,000 miles! I change them at every other oil change (2,000-mile intervals) just like I do with my other bikes. My thinking is you can’t be too careful with a bike this old and oil is cheaper than having to rebuild the engine or transmission. If for some reason I don’t ride the bike 1,000 miles in a year, I’ll still do a full maintenance cycle (all oils) during my regular winterizing schedule.

1976 R 90/6: For my Airhead, the owner’s manual specifies an engine oil change (and filter, of course) every 5,000 miles (“Minor Service”). When it comes to gear oil for the transmission, swing arm and final drive, the interval is every 10,000 miles (“Major Service”). Like the Slash 2, I use a more aggressive maintenance schedule. I do the engine oil and filter every 2,500 miles. Even though I don’t have to, tend to change the gear oils at the same time because I’m working on the bike anyway and again, oil is cheaper than rebuilding the transmission.

2015 R 1200 GS: BMW Motorrad’s engine oil change interval for my modern bike is 6,000 miles. I use a 5,000-mile interval because 5-10-15-20 is easier to remember than 6-12-18-24. This interval may be different for K bikes and the very newest boxers; refer to your owner’s manual. The oil change interval for the final drive is 12,000 miles, but it takes such a small amount of oil that I already have available that I just change it every 5,000 miles when I do the engine oil.

It should go without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: Recycle your used oil. My local dump takes used oil and there are auto parts retailers out there that will take your used oil as well. You could also check with your local motorcycle dealer or repair shop. Some industrial businesses will also take your used oil, as they use it to heat their facilities, but you’d really have to research to find these or happen to know somebody who works there.

Now let’s take a look at the cost for a single full maintenance cycle. To me, that means any oil that can be changed gets changed, and the bike gets a fresh oil filter, too.

| 1966 R 60/2 | 1976 R 90/6 | 2015 R 1200 GS | |

| Engine oil, qts* | 2 ($20) | 3 ($30) | 4 ($40) |

| Oil filter | No | Yes ($22) | Yes ($26) |

| Gear oil, qts** | 2 ($25) | 2 ($25)** | 1 ($14)** |

| Crush washers | 7 ($8-10) | 7 ($8-10) | 1 ($2) |

| Other | N/A | Oil filter cover gasket ($9) | O-ring for final drive drain ($2) |

| Approx total | $55 | $96 | $84 |

* Refers to quarts needed to do the oil change, not the oil capacity of the system, which may be less than the quarts needed.

** I use the same gear oil on these two bikes, which mitigates the overall cost.

Before You Email Me

I am not claiming there is only one correct oil for a given application, because there are many brands and formulations that can work just fine. I am not claiming synthetic oil is harmful to older engines, transmissions or final drives; what really matters is additive packages, oil change intervals and mechanical condition. It doesn’t matter whether the base oil starts in the ground or a laboratory. I am not claiming detergent oil will damage older engines, but I am claiming you have to know what state your slingers are in if you’re going to use it. I am not claiming GL-5 gear oil is always unsafe to use in older motorcycles, just that you need to understand your gearbox components and the chemistry of your chosen oil. I am not claiming that name-brand oil is somehow magically superior to brands I’ve never heard of, but I will claim those oils have more consistency, better accountability and higher standards because the reputation and market success of the company on the label relies on it.

Above everything else, I am not claiming that oil discussions are simple. Oil is a complex substance and true experts spend years studying chemistry, metallurgy and real-world applications. I’m here to offer you honest, reliable information and practical, middle-path guidance. Don’t treat this article as definitive or the last word on oil.

References

American Petroleum Institute. “Oil categories.” https://www.api.org/products-and-services/engine-oil/eolcs-categories-and-classifications/oil-categories#tab-gasoline

“Castrol oil engineer Paul Beasley.” Chasing the Horizon from Wes Fleming, 6 May 2018, https://horizon.bmwmoa.org/2018/05/episode-21-paul-beasley/

Collins, Danielle. “Hypoid gearboxes: What are they and where are they used?” 18 October 2017. https://www.motioncontroltips.com/hypoid-gearboxes-what-are-they-and-where-are-they-used/

Haas, A.E. “Motor oil university,” 21 March 2011. https://bobistheoilguy.com/motor-oil-101/

Penrite Knowledge Centre. “Viscosity.” https://penriteoil.com.au/knowledge-centre/Viscosity/237/what-is-an-sae-viscosity/180

Widman International SRL. “Motor oils.” https://www.widman.biz/English/Tables/gr-motores.html