The first time I had heard of Japanese whisky was over a decade ago while on vacation in Texas nursing an afternoon Old Fashioned and scrapping with the chatty bartender about American versus Celtic whiskies. He got busy with something and disappeared for a bit then announced his return by sliding a new glass my way with a big smile on his face. “Try this.”

For a long time, Scotch was the standard. It had the history, the climate, the craftsmanship. If you wanted to drink the best, you drank Scotch. Then something changed. Not overnight, but steadily. Japan started making whisky that could compete—and win.

In 2001, a Japanese whisky beat out the world in a blind taste test by Whisky Magazine, taking their top prize. Since then, distilleries like Suntory and Nikka have become household names to whisky fans everywhere. Their bottles now regularly place at the top of competitions from San Francisco to Glasgow. The old assumptions about who made the best no longer held.

But this didn’t come out of nowhere.

What Sets Japanese Whisky Apart

Japanese whisky started as a faithful replica of Scotch. The techniques, ingredients, and even the spelling of “whisky” were carried over from Scotland. Early distillers studied in Scottish distilleries, used pot stills, and in some cases imported barley and equipment directly from the source. So on paper, Japanese whisky and Scotch look very similar.

But over time, Japanese whisky developed its own identity.

The climate in Japan is more variable—humid summers, cold winters—which leads to a more dynamic aging process. Japanese spring water, often sourced from mountains or natural springs, brings a softness and clarity to the whisky’s texture.

Mizunara oak, native to Japan, is another hallmark. It’s difficult to work with and takes decades to mature, but it contributes unmistakable flavors: sandalwood, incense, and subtle spice.

The approach to blending is different too. While Scotch blends often combine whiskies from various companies, Japanese distilleries typically produce a wide variety of styles in-house to blend internally. That allows for a more controlled, nuanced final product.

In terms of taste, Japanese whisky is generally more restrained. Where some (but not all, a common misconception) Scotch whiskies lean heavy on peat, brine, or sherry richness, Japanese expressions tend to aim for delicacy and detail. You might notice floral notes like cherry blossom or iris, green apple, honey, or a touch of white pepper. Peat is used, but with a lighter hand. It often feels quieter on the palate—less about hitting you with one strong flavor and more about evolving layers.

It’s not simply Scotch made somewhere else like “sparkling wine” not from Champagne, France. It’s whisky made with a different perspective.

How It Started

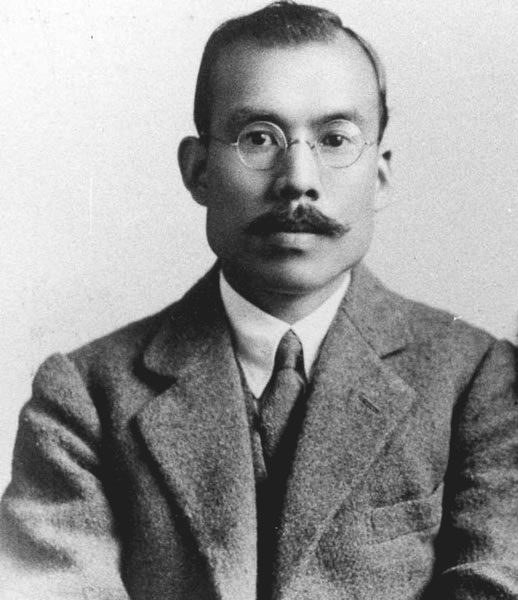

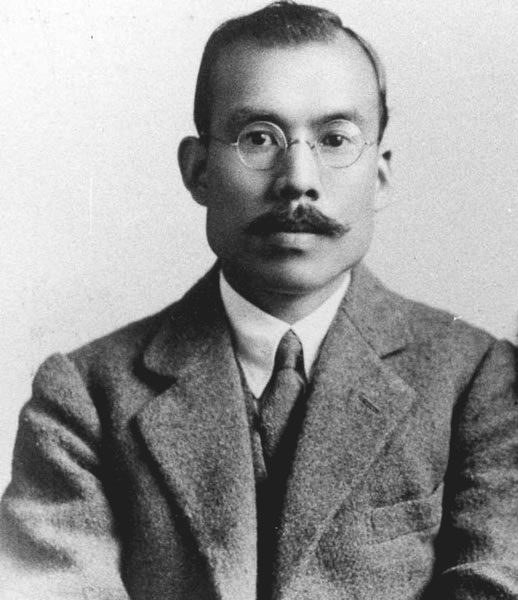

The roots of Japanese whisky go back to Shinjiro Torii, a pharmaceutical wholesaler who opened a wine shop in Osaka in 1899. He eventually shifted to domestic spirits, and in 1923 he founded Kotobukiya—which would become Suntory—and opened Japan’s first whisky distillery in Yamazaki.

Torii had help. Masataka Taketsuru, a young chemist, traveled to Scotland in 1918 to study chemistry and learn the craft of whisky-making firsthand. He apprenticed at distilleries across regions like Speyside and Campbeltown, taking detailed notes along the way. When he returned to Japan, he partnered with Torii and helped launch Suntory’s first whisky in 1924. A decade later, Taketsuru left to open his own distillery, Yoichi, in Hokkaido—a place he chose because its weather reminded him of Scotland.

Today, Suntory and Nikka are the two giants of Japanese whisky, and it all started with these two men.

Distilleries to Know

Just as the whisky regions of Scotland produce dramatically different flavor profiles due to local conditions and natural resources, Japanese whiskies benefit from the specific environments of their distilleries.

Take Yamazaki. The distillery sits just outside Kyoto, surrounded by forests and spring water. Torii believed good water made good whisky, and Yamazaki is known for its soft, clean minerality. They use a variety of still shapes to create whiskies with different profiles, and they age many of their expressions in the previously mentioned Mizunara oak giving it a distinctive flavor.

Then there’s Hakushu, launched in 1973 in the Japanese Alps. The high altitude and cool climate give its whisky a freshness and light smoke that stands out. Hakushu and Yamazaki whiskies are often blended into Suntory’s award-winning Hibiki line.

Over at Nikka, Yoichi remains fiercely traditional. They still use coal-fired pot stills—a method almost entirely abandoned elsewhere—because it adds a bold, smoky character. Miyagikyo, Nikka’s second distillery, opened in 1969 in a lush valley outside Sendai. It produces a softer, fruitier whisky that balances Yoichi’s intensity.

A younger distillery, Chichibu, founded in 2004 and operational by ’08, has quickly gained attention worldwide. With small-scale production and a hands-on approach, its whiskies are already highly collectible.

A Note on Scarcity

The increased reputation of Japanese whisky has placed it in high demand, and many of the bottles that were once affordable and available have become hard to find. Some age-statement expressions, like Hakushu 12 or Yamazaki 12, were even pulled from production for a few years because there just wasn’t enough mature whisky to bottle. Some are back now, but prices have risen. Hakushu 12 returned to shelves in limited releases starting in 2021, but availability is still tight.

If you’re just getting started, look for non-age-statement expressions like Suntory Toki, Hibiki Japanese Harmony, Nikka Days, or Nikka From the Barrel. These are easier to find and still offer a great introduction to the style.

Where to Start

Here are a few recommendations if you’re new to Japanese whisky:

Hibiki Japanese Harmony

Created to carry on the Hibiki line after aged expressions like the 17 and 21 became harder to produce, Harmony is a blend from Suntory’s three distilleries designed for balance and elegance. It’s smooth, floral, and approachable, with notes of orange, chocolate, light oak, and a touch of smoke. Great neat or in a highball. Usually $80–$110.

Nikka From the Barrel

A blend with depth and spice. Bold, fruity, and warming. Look for notes like clove, cherry, and toffee. Widely available, usually around $80–100.

Nikka Coffey Grain

Made in traditional Coffey stills. Sweeter and smoother, almost bourbon-like. Expect flavors of vanilla, tropical fruit, and caramel. Around $55–90.

What’s a Coffey Still?

A Coffey still (pronounced “coffee”) is a type of continuous still invented in the 1830s by Aeneas Coffey. Unlike traditional pot stills, which work in batches, a Coffey still can distill continuously, producing a cleaner, softer spirit. That makes it ideal for delicate, sweet grain whiskies.

While some Scotch distillers still use Coffey stills for grain whisky used in blends, most single malts rely on pot stills for their fuller flavor. In the US, modern column stills have evolved from the Coffey design, but they’re built for volume, not nuance. Nikka is one of the only distillers in the world that uses traditional Coffey stills to create whiskies that are bottled and celebrated on their own—like Nikka Coffey Grain and Nikka Coffey Malt. These offer a smooth, almost bourbon-like experience with distinct notes of vanilla and caramel.

Suntory Toki

Light, easy-drinking, and affordable. Great for highballs. Soft hints of apple, basil, and honey. Often under $50.

Hakushu 12 (if you can find it)

Fresh, lightly peated, and complex. You might taste pear, mint, and faint smoke. Usually $160 and up.

Yamazaki 12 (if you can find it)

Soft and layered with fruit, oak, and spice. Notes of cinnamon. Often $160+, depending on demand.

Learn more:

function loadFBE(){console.log('load fb pix');

document.removeEventListener(‘scroll’,loadFBEsc);document.removeEventListener(‘mousemove’,loadFBE);

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t, s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window,document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘501747083364621’);

fbq(‘track’,’PageView’)

}function loadFBEsc(){if(window.scrollY>57)loadFBE()}document.addEventListener(‘scroll’,loadFBEsc);document.addEventListener(‘mousemove’,loadFBE)